In the media: Rarity – Personalised cancer treatment – fact not fiction

Imagine a world in which each person’s cancer is treated with a personalised, targeted medical treatment regimen. A world in which each cancer battle were being fought within a framework of a detailed understanding of each individual cancer. It is well documented that cancer is the leading cause of death – worldwide. In 2020 nearly 10 million people lost their lives to cancer (WHO Fact Sheet, Cancer, Feb 2022). In recent years important progress has been made to try reducing the cancer burden through awareness campaigns targeting known cancer risks, pre-cancer screening protocols and early detection and diagnosis. But whilst it is vital that the correct cancer diagnosis is established in order to plan appropriate and effective treatment the current diagnostic process is in fact limited in terms of truly testing, identifying and understand the specifics of the cancer that each person has. But Hans van Snellenberg is on a mission to change that. A deeply personal mission to fully utilise the exciting advances in science, technology and medicine to change the way we treat cancer, worldwide.

Hans is the managing director of Hartwig Medical Foundation, which is based in the Netherlands. The Foundation uses cutting edge technology to drill down into the DNA of cancer tumours, generating a full genome sequence, which in turn offers all treatment options and prospects for cancer patients. For Hans, one of the driving forces behind this exciting new development in the treatment of cancer, the journey started as a deeply personal one when his own father was diagnosed with cancer. For Hans the impact of his father’s cancer changed the course of his career, benefiting and changing the treatment for cancer patients now and in the future.

“It started all in December 2005. My father was diagnosed with cancer, which was already metastatic in the liver and lymph nodes. The prognosis was bad. The hospital options for treatment were poor. They stated that they could try chemotherapy. You are confronted with a disease where you only have maybe a year to live, and then a doctor says we can try a therapy such as chemotherapy, but, only three out of ten people will have a positive reaction to it, the remaining patients will have negative effects and will probably have a reduced quality of life for the remainder of their life. My initial reaction was how is it possible after we invest so much money into cancer research and the best outcome we have is to say only 30% of the drugs are efficient.

That was the start of my exploration with my father. We wanted to find out why the treatment was so limited and generic. After visiting doctors in the Netherlands and abroad we found that the drugs and therapy offered were just guidance. Treatment offered was based on the location of the tumour like lung cancer or stomach cancer but if you look at developments since the late 80s, the knowledge now is that it’s not so much the location of the tumour, it’s much more the DNA mutation which is causing cancer to grow. It could be the fact that things that happen with women in breast cancer for example are the same things that happen with men in stomach cancer. So rather than putting a drug on the market only specialised for a certain type of cancer you could look at the mutation of the tumour. The genetic makeup of the tumour and treat it.”

Unfortunately Hans’ father died 10 months after diagnosis. But his death was a starting point for Hans to begin to raise money along with four others for the University Medical Center Utrecht. He had met prof dr Emile Voest, a highly respected oncologist and was committed to raising money for the research of the genetic make up of tumours, and the efficacy of drugs. To ultimately give cancer patients the chance of a better prognosis.

“We hoped to discover what types of drugs worked best for different types of tumours. But back in 2008, there were only a few centres and researchers in the Netherlands that were working on that issue. Emile contacted prof Edwin Cuppen (human genetics) in Utrecht and they were clear on what they needed for their research. They needed a sequencer. I had no idea at the time what that was but learnt simply it reads your DNA. A sequencer costs over 400,000 euro and that of course is a huge amount of money. We raised that money over the next six to seven months and bought the sequencer.

This was not the end of what was needed by the centre, next were chemicals and sundries plus personnel etc. We then realised this was so much bigger and our fundraising was not over. We set up a foundation called Barcode for Life. The Foundation raised money, on average 400 to 500,000 euros a year, just to fund the lab and research. The centre grew and started working with other centres, one in Amsterdam and one in Rotterdam and it continued to grow until we ended up working with 12 centres.”

In the period of 2008 until 2014 the initiative grew step by step after meeting a Dutch philanthropist who agreed to help sponsor the research conducted with the patients who took part in the DNA sequencing. After suggesting that a purpose-built, high tech lab would be a more efficient way to operate (after 4 years of research their work was spread over 12 hospitals) Hans, Edwin and Emile began looking at the associated costs for this proposal. They concluded that a budget of around 30 million euros would be needed, and incredibly, this was granted by the philanthropist.

However, the funding was given with the stipulation that guys who made the plan also should deliver, and so Hartwig Medical Foundation was born. In 2015 Hans left his job and alongside Edwin Cuppen, a professor in Human Genetics started running the foundation. Speaking about this remarkable decision to become the full-time Managing Director of the foundation Hans reflects that;

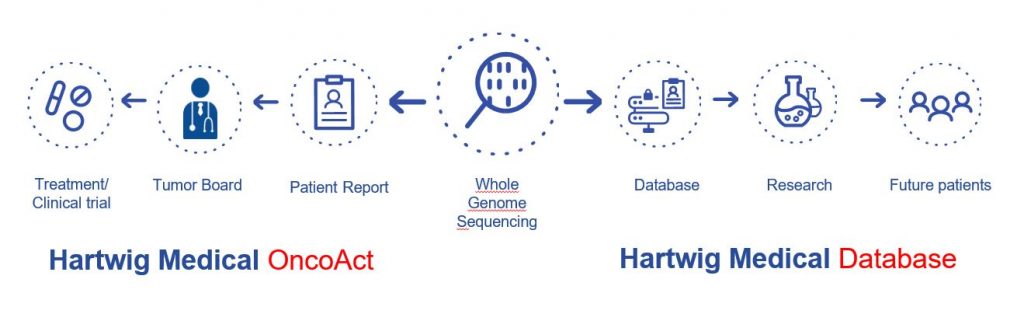

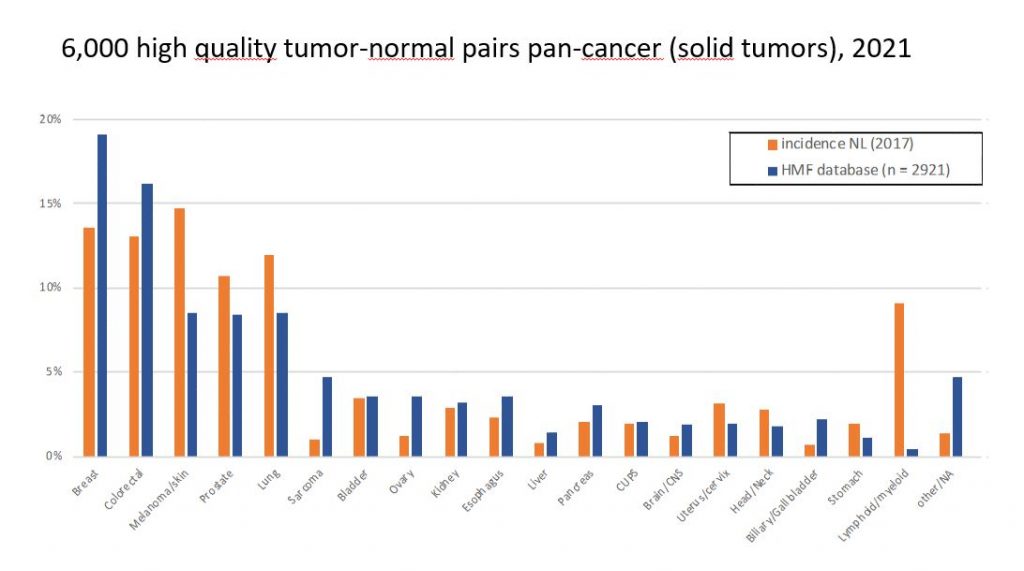

“I previously worked in finance and IT so I think in retrospect, it was a very bold move but I didn’t notice at the time because I just felt I had to do it. This was an opportunity and I wouldn’t get another chance, especially with so much support from people that believe in it. Of course, we had our setbacks too but it is still driving innovation in healthcare in the Netherlands. We started with an empty room, no sequencers no staff – but we built up the foundation. We started a database which now contains data (genetic data and clinical data) of over 5000 patients which made it possible to develop an algorithm to stratify cancers of unknown primary. What we also developed was a very complete DNA test, which is, I think the most comprehensive test there is for cancer.” Hans went on to explain that “Hartwig Medical Foundation has two separate sides in effect, you’ve got the database, which is the gathering of the information and the processing of it and then the genetics DNA side. In over 60% of cases, we can predict the tumour type plus if we add in data shared from the pathology departments that can add in an extra 20% so together this gives a better view of which type of tumour it is. The information on the database was collected from patient data coming in from the hospitals we already worked with, and the rest of the data was from the clinical studies we support.”

The work is a two-step process. As Hans explains, “first the DNA sequencing is done, billions of pieces of genetic information is held in your DNA and the sequencer is able to read it all, every single one. The samples are taken out of your blood, which is your good DNA, and out of the tumour biopsy. This way you know what is going wrong, and you can find the mutation between your good DNA and your tumour DNA. The second step is the data component. The results from the sequencing are imputed into Hartwig Medical Foundation’s IT software pipeline. It is analysed and comes up with a treatment guidance based on the DNA. A report is produced and will give the details of the tumour and also the guidance for the treatment. Anybody in the world who would like to use that software pipeline can do so. It is easy to use the software and is packaged for use on the Google Cloud Platform. This enables anybody to get the DNA sequencing done in their own country before accessing the software pipelines. The more people that use the pipeline the more data is collated making treatment options clearer. The options for treatment could be traditional or from off-label treatments or experimental treatments that could in effect raise the treatment effectiveness from 30% to more than 60%. This is a huge leap forward for cancer treatments. If there are no treatment options, and sadly this will also be the case sometimes, your time can be spent living your life to the fullest without using a treatment that is negatively going to affect your remaining time.”

For Hans one of the most important outcomes of their work is the provision of a treatment plan that could offer the best possible outcome for the person needing the treatment. Using the example of breast cancer Hans explains exactly the way in which we can improve treatment. “With our data research is done by the Erasmus Medical Center on 700 breast cancer patients. Looking retrospectively at the data (because you only can look at the data that you have generated) you can see that there are different tumour profiles in that group.

For instance, for breast cancer, there are many therapies and they’re always given in order. For example treatment one is given first and if you do not respond, you go to treatment two, and then to treatment three etc. It is sequential decision making. But if you look at the different tumour profiles, you can see that some tumour profiles responded much better to the different treatment options than others. So for certain tumour types you should skip treatment one and go directly to two.”

Hartwig Medical Foundation shares their data with other research organisations around the world, to date over 200 data requests and 80 institutions worldwide are working with the data held by Hartwig Medical Foundation. Access to the data is given under strict GDPR criteria (General Data Protection Regulation) because of the sensitivity of the DNA data, and the Foundation requires a signed license agreement. Any requests for the shared data will go through a scientific assessment. A Data Access Board made up of a panel of independent experts looks at each request taking into account what the research it is being used for and considers the legal and ethical aspects of the requests. The data Hartwig Medical Foundation has created is a crucial part of the drive to improve cancer care and treatment worldwide, which is why Hartwig Medical Foundation is committed to sharing and growing the database ethically, and in the best interest of cancer patients.

Hans is very passionate about the care and treatment of cancer patients and believes that things can and should continue to improve as knowledge and understanding of the DNA of cancers is researched, and better understood. Technology is driving forward changes to the treatments offered to patients, but there is room for much improvement across the board when it comes to offering the best options to each patient. A one size fits all treatment plan is, quite simply, neither good enough, nor the answer.

Hans believes that “it really shouldn’t matter in which hospital you are treated, you should get the best diagnostics there is and good analysis of your primary tumour, sadly this is not always the case. This is one of the main reasons we are driving this change so much because currently, it depends on which hospital you are treated in and what kind of diagnostics are done. After all, we all pay the same insurance fee so we should have at least the same level of quality of care. Of course, there are very good doctors but at least having the same type of diagnostics, in every hospital would be important for patients. The other point in cancer care I don’t understand is the treatment offered that would only work for 30% of patients. I can understand that having a drug that works for 30% is better than none at all but nobody in the whole system seems to be pushing for a bigger efficacy say 50%.”

Hans and his team are clear that one way in which to work towards a better treatment model for cancer patients is through creating a standardised process for all hospitals to follow. “If it’s standard that your data, your diagnostic data, your genetic data, and your clinical data are put into the database, then you have a very powerful instrument to see all 40,000 patients with metastatic cancer in the Netherlands, we can see the treatments and also the success rates of treatments. If we have that 40,000 every year in our database, it would also be much easier to compare to others. For example, if someone comes to the hospital with an unknown primary we could check to see if there is anybody else who has the same type of tumour or characteristics of the tumour. This, in turn, will improve the treatment options for cancers.”

The scope of the database could help plan better treatment options for all cancers – from the very rare to the five main cancers; breast , colon, prostate, lung and skin cancer. For example all cancer types will have subgroups of patients who will react differently to the treatment options. Capturing and sharing this across a national database could mean that different treatment options that might work, or even different drug dosages and the type of drugs used, could be more readily identified. It is truly ground-breaking work that has the potential to change the way cancer care is offered worldwide, creating a more personalised cancer care specific to the patient.

Hans’ drive, passion and positivity is inspiring, and the shared commitment of the Hartwig Medical Foundation team to drive forward the advancement of cancer care has created a momentum for change that offers real hope. And as Hans explains, “the good thing about our work is it only has benefits. It has benefits for patients because they’re treated better, there are benefits for doctors because they have more possibilities to do the diagnostics and find out which drugs are okay. It’s better for the healthcare system because you do not treat patients with drugs that don’t work. The drug efficacy will be better. It’s very fulfilling to work on this. It’s a story of doing good things together. And we need everybody aiming for the same goal, we need the clinicians, we need the patients and organisations, we need hospitals and regulators for this.”

Read the article in Rarity

You read an article in the category Uncategorized. You may also be interested in Hartwig Medical Foundation, Learning healthcare system, Molecular diagnostics, Personalized treatment, Rare cancers, or Whole genome sequencing.All news

Also read

Take a virtual tour of our laboratory: from the biopsy to the patient report

What happens to your tumor tissue and blood during a comprehensive DNA test? What exactly does all the complex equipment …

Join us for an evening of Healthcare Tech innovation with Hartwig Medical Foundation and GCUG

Calling all software developers and tech enthusiasts 🚀 Hartwig Medical Foundation partners with Google Cloud User Group (GCUG) to bring …

GLOW: working toward more treatment options for glioblastoma

The outlook for patients with glioblastoma has been unfavorable for years, and treatment options remain limited. That is a reason …

The complete DNA test provides a complete overview of all potential targeted cancer treatments. The patient and the attending physician have all available information to make a treatment decision.